Dear Reader,

It’s no secret that I’m publishing this after something of a prolonged dormancy here on Substack. But, not unlike a sleeping bear, do not mistake my winter dormancy for defeat.

Until December of last year, I had been publishing weekly. A schedule I was proud of. Even still, I couldn’t shake a subtle but nagging judgement. Worthwhile as my weekly articles were, it felt as if I was in some way motivated by the same force that I believe lies at the root of the climate crisis. A force that predates the tracking of atmospheric greenhouse gases or global average temperatures. The same force that author and environmental humanities scholar, Rob Nixon, calls the cult of speed.

The Cult of Speed

A hallmark of this cult is the myth of perpetual growth. Even mainstream climate solutions betray a bias towards this growth mindset, believing we can simply grow our way out of the problem of an increasingly hotter Earth. Case in point, in each of their reports since the Paris Climate Accord, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has relied on “negative emissions technologies” in order to hit their proposed targets. The models cleverly integrate solutions like carbon capture that are theoretically possible but have yet to be proven at scale. The same reports prejudice practical solutions, like a moratorium on new fossil fuel infrastructure, or weaning the global rise in the consumption of red meat, because to do so would antagonize dominant economic sectors.

But I’m not here to throw the climate-aware contributors to the IPCC under the bus. Rather, it would seem that despite our know-how, certain fundamental beliefs have a great deal to do with the solutions we are willing to consider. We need only look at the current administration running roughshod through the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health to see that scientific understanding is only has useful as it is employed. But if we truly reckon with what planetary science has been saying for decades, the safe, stable, and secure future we dream of will almost certainly demand cultivating a slower pace of life. Particularly amongst those of us who call the global north home.

Taking my own advice, I decided to investigate my intuition that a slower, more methodical writing process might widen the aperture with which I relate to the climate crisis and cultivate a space more conducive to entertaining its many solutions. So, I bought a legal pad and began drafting the_slow_times by hand. Despite needing to adjust to a slower editing process, handwritten drafts have already begun to help recontextualize the_slow_times to better reflect the pace that I believe germane climate action must embody.

Allow me to shed some light on how things will look moving forward…

Why now?

As for the impetus of this shift, I’m hardly alone when I say Donald Trump’s reelection served as a massive reality check. It forced me to reconsider a lot of what I wanted to believe was on the horizon relative to climate action. In moments like this, I tend to read more than I write. Eager as I am to offer my two cents, it’s usually better if instead I dip my cup in the well of wisdom before stewing with my thoughts on an empty page. One such resource was Rob Nixon’s seminal book, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.

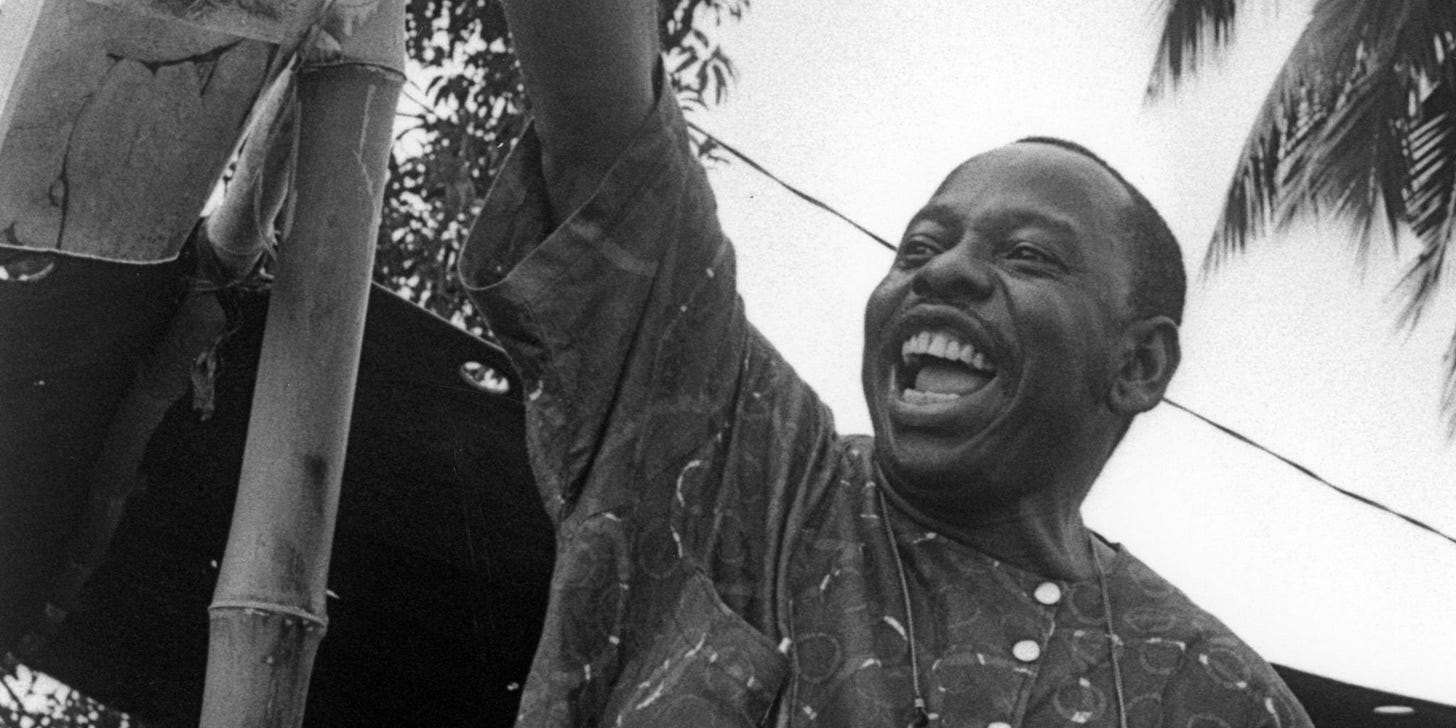

It escapes me quite when I first encountered the book but it was hardly coincidental that an unprompted hiatus began around the same time. As if jolting me from the perceived necessity of weekly posts, I found myself humbled by Nixon’s literary analysis that weaved together legacies of environmental writers from the last century. Legacies like Rachel Carson’s iconoclastic treatise on our ecological interdependence in Silent Spring, and Ken Saro-Wiwa, Nigerian author, Ogoni folk hero and martyr, and founder of the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People (MOSOP), from whose smuggled prison letter came the impassioned proclamation “the environment is man’s first right.”

The legacies of these “writer-activists,” as Nixon dubbed them, grounded me in a moment of untethered despair. But Nixon’s central thesis did more than connect me to a rich history of environmental soothsayers. He named something I had been wrestling with for a while, but that I had resisted engaging with directly because moving fast offered a palliative effect. Defining his titular premise, Nixon zeroed in on what is so painful about the climate crisis:

“By slow violence I mean a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.”

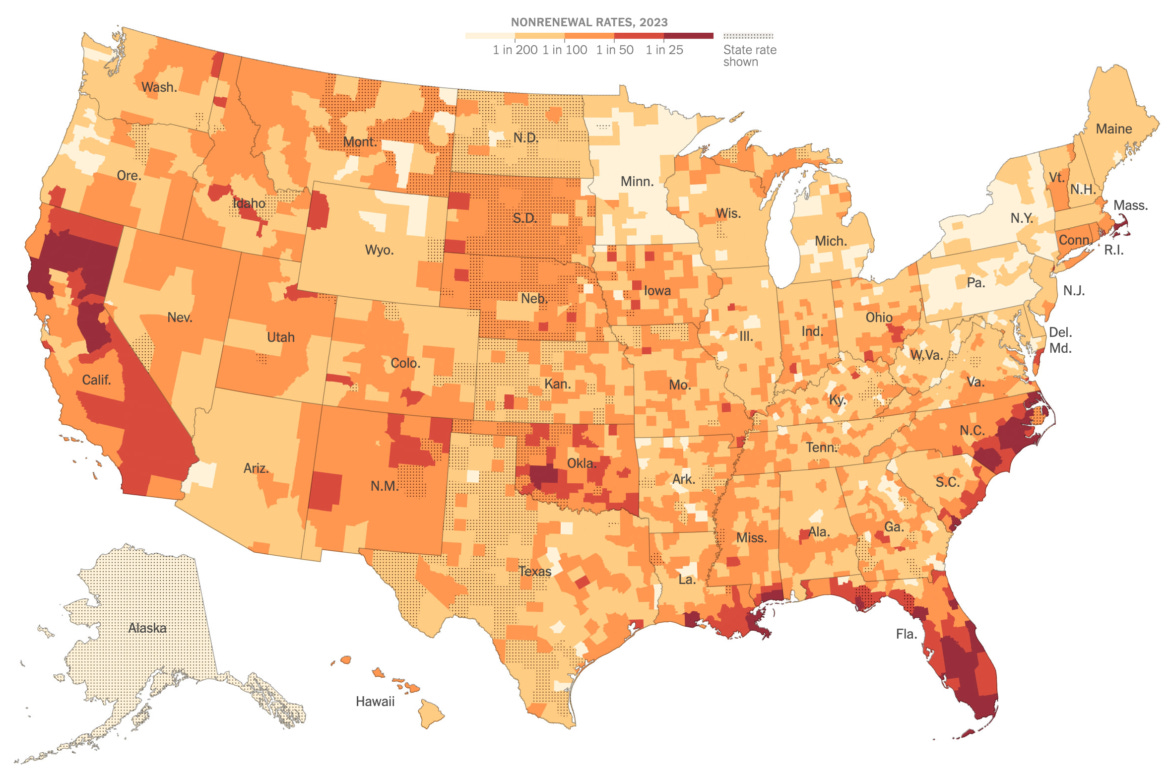

Published in 2011, reading Nixon’s book today brought more than a decade’s worth of slow violence into stark focus. Flammable sinks followed our newfound capacity to frack for natural gas and otherwise inaccessible oil. And unseasonable rainfall continues to threaten crop yields each year. All while increased storm intensity and the creeping threat of wildfires that no longer discriminate between the wet or dry season fuels a state-by-state insurance exodus under the pretense of “smart business.”

Hindsight has the unique capacity to illuminate trends that don’t always appear obvious in real-time but merit vital consideration as we step into an increasingly uncertain future. Increasing our awareness of the slow violence of the climate crisis by leveraging climate writing of the past is exactly what I want to lean into with the_slow_times.

I loved hearing this intuition echoed recently by climate corruption journalist and podcast host, Rachel Donald, during her conversation with energy historian, Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. Towards the end of their discussion, Donald makes the following point:

“It always seems to me, when having conversations like this, like [we must] use the past in order to understand the big picture, because the present is, I mean, it's so much more complicated now.”

And therein lies the challenge. The climate crisis has always been an intersectional, force-multiplier. Which means that with each passing year we find ourselves within an increasingly complex and convoluted set of systems. Every angle from which to view the climate crisis is competing for our scarcest resource yet: our attention.

So, what are we to do? Diversify. We need as rich a diversity of climate-related content as we do species in the most biodiverse regions of the planet. That is how we propagate the ideas that will change the world for the better. Our strength is our diversity.

Donald’s own tenacious coverage with Planet Critical is in part what prompted me to reconsider my own tactics with the_slow_times. While there is a need for timely, accountable reporting, like Donald’s Planet Critical, Carbon Brief, or Emily Atkin’s incredible newsletter Heated, I am excited by the thought that the_slow_times can compliment these outlets by engaging with questions of pace and ask how we might begin to feel our way out of this world and into the next.

What will the future hold?

When I first set out to write the_slow_times, I initially referred to it as “journalism for a climate-changed world.” Fundamentally, I still believe this. We can’t afford to discuss climate change as some future state of the world. It is here and now.

Described by philosopher Timothy Morton as a hyperobject, climate change is so pervasive in fact, that it’s literally difficult for even the most civically and scientifically engaged to keep it top of mind. There is no outside. Our entire lives exist within its scope, like fish in water.

To be fair though, how many fish do you know that read about water? Very few, I imagine. Because they’re understandably concerned with the immediacy of issues like why their food is disappearing, why is no one building more coral, or why the hell is this clown fish playing supreme ruler?!

All the more reason then to reconsider how it is we engage with the subject matter. Because the water in which we swim matters.

Moving forward, the_slow_times will no longer adhere to a weekly publishing schedule. Instead, the bulk of my writing will shift to long form content, like investigative articles and reported essays, exploring the climate crisis and adjacent topics through a variety of lenses like politics, history, psychology, and culture. the_slow_times will be defined not by its frequency, but by its deliberate commentary and reporting.

Suggestions are always appreciated, but here are some of my guiding questions:

What can we glean from climate writing of the past?

How might we slow down as individuals and as a society?

What would a slower world even look like?

What contemporary examples can we draw from to cultivate slow time?

That said, as I was exploring new tactics, someone I have a lot of respect for told me the_slow_times was one of only a few sources of climate-related news that they engage with regularly. To be honest, that blew my mind. But it also made me realize something important. Amidst my own efforts to stay informed, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that many have limited bandwidth with which to seek out climate stories. So, as eager as I am to explore the cultural implications of the climate crisis, I want to make sure the_slow_times still provides a dose of timely news and current events for my small but fertile audience. That is where Substack Notes will come in.

Substack Notes is the perfect tool to provide short form content like links to other outlets and articles worth checking out, podcasts I’m enjoying, and excerpts from recent research. Notes from the_slow_times will get pushed to your general Substack feed as well as nestled under their own tab on the_slow_times dashboard to be viewed at your convenience.

Embracing Slow Media

“The past ten years of interviews have shown us how media should be slow, rooted, and steadying, and this shift to slow media honors all that we have learned from years of beautiful conversations.” — For The Wild

Models already exist of the “slow media” that I hope to emulate with the_slow_times. Outlets like UK-based Delayed Gratification have long championed the “slow journalism” movement. Popular podcast and progressive media outlet For The Wild has also helped cultivate the space.

At the end of last year, For The Wild went so far as to inform their listeners they could expect a shift in programming that would better match “Earth’s pace.” It is my hope that the_slow_times will mature, patiently, into a contemporary adjunct amongst these and others working to nurture this alternative climate (s)pace.

A Vintage Vantage

Something I know I’ve been guilty of in my own coverage has been focusing on the severity of climate impacts that are still to come even under the best case scenarios. True as it may be, that reality can also be powerfully demotivating. Worse still, humans are incredibly adaptable. Which means we’re pretty bad at registering subtle changes as they take shape. That is to say, banking on worsening future states to motivate action is hardly a reliable strategy. But if my hunch is right, I believe that by shining a light on the wisdom of the past, like Nixon and others, we can better equip ourselves to stem the slow violence of climate change.

Like the rings of a tree offer a glimpse into the climate of the past, I envision the_slow_times serving as a similar record of our awareness of the climate crisis. I remember twenty years ago having to carefully broach the subject of climate change as if it were a fringe concern. But the climate crisis is no longer avoidable — despite our meager response. Too often though the visceral nature of reporting in the present can obscure the fact that many saw these impacts coming. If we don’t take the time to learn from our recent past, and heed the warnings of tomorrow, there is little reason to think we’ll look back in another twenty years with anything but contempt for our continued paralysis.

I like to think of it as seeking out a vintage vantage. Like thrifting the perfect midcentury chair, or your father’s heirloom denim jacket, vintage implies a unique value that persists through time. That’s why the_slow_times will strive to draw from vintage voices whose persistence on this beat has stood the test of time.

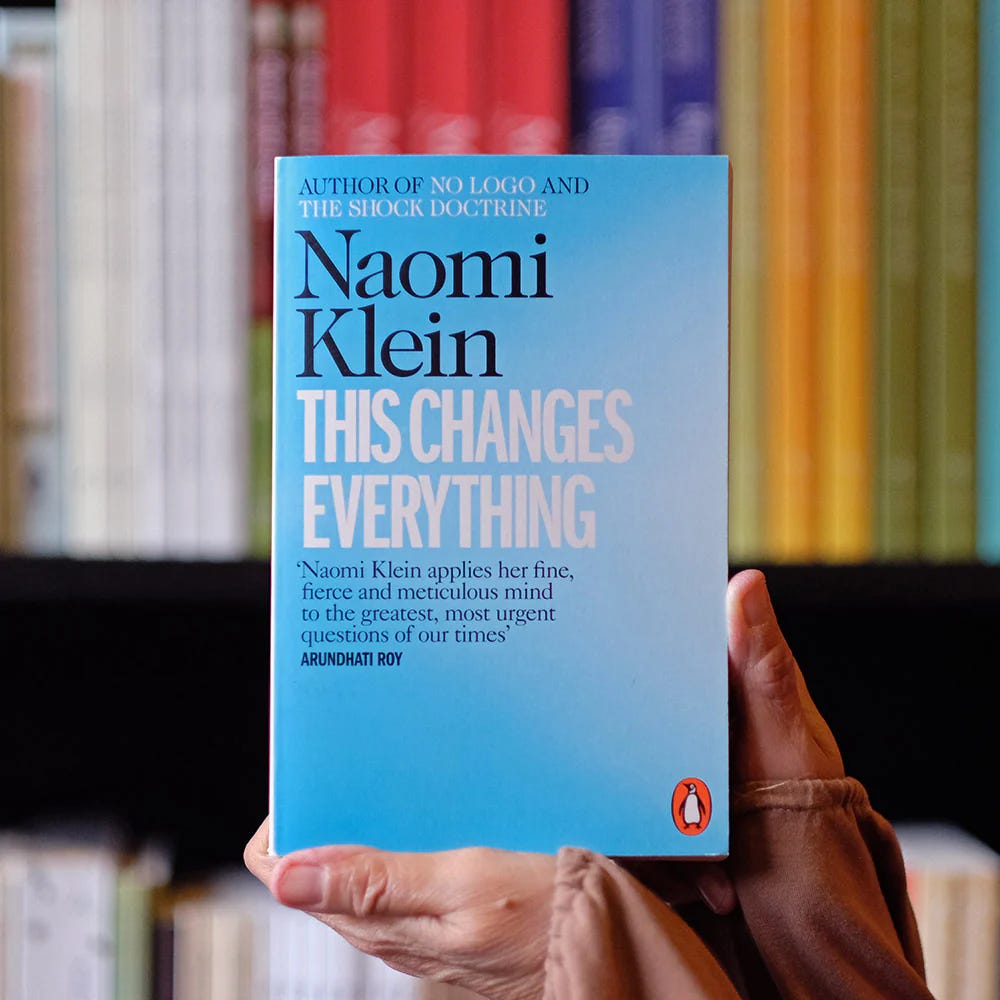

A perfect example of the clarity the past can provide is Naomi Klein’s first book to tackle the climate crisis, This Changes Everything. The weight of Klein’s reporting reads quite differently today than when it was published over a decade ago in the pre-Trumpian era. It illuminates something that the forward march of science can at times obfuscate: We have long understood the fundamentals of the climate crisis. What we have lacked for far too long is the political will to act on the scale commensurate with our awareness.

But the irony of suggesting we meet a moment of crisis by intentionally slowing down is not lost on me. To some, it may sound like I’m advocating for a withdrawal from the decades-long struggle for bold climate action. An elegiac retreat into the woods, if you will, until all that’s left are private logging plantations. But to confuse advocating for a slower society with an appeal towards romantic pastoralism is to lose the forest for felled trees.

On the contrary, to call for a slower pace on a hurried planet is, in fact, bold.

Triage

That we even refer to the climate as in a state of “crisis” warrants reconsidering our tactics. The origin of the term comes to us from early Greek medicine, denoting the moment at which a patient’s outcome could be understood as binary: recovery or death. Anyone familiar with medical triage can appreciate the risks of unencumbered speed in times of crisis. Personally, I’ll never forget learning this lesson.

Handed down over decades of backcountry education as the founder of both Outward Bound and the National Outdoor Leadership School, Paul Petzoldt’s first piece of advice in any backcountry emergency was, of all things, to smoke a cigarette. Because the worst way to antagonize any emergency is to join it.

I became privy to this sage wisdom during a wilderness medicine course decades after the Petzoldt era, but my instructors were equally blunt. Before acting on our training, they stressed the value of first taking the time to slowly assess the situation. One thing you become acutely aware of traveling in the backcountry are the many ways in which simple risks pose grave threats. A shifting boulder can easily trap the only capable responder. While the Wilderness Medicine Institute no longer endorses the “Marlboro minute,” their general message has otherwise remained unchanged: Take time to assess before rushing to action.

Even as I write this though, I can feel my own predisposition to immediacy percolating. But having had to put this lesson into practice while staring past ligaments and tissue into a lacerated forearm, revealing the ghostly white bone of a fellow hiker I had just met at a remote campsite along California’s Pacific Crest Trail, I have no choice but to trust this timeless wisdom.

Not to mention, it continues to rear its head.

“The times are very urgent — we must slow down.” — Bayo Akomolafe

In an essay following an appearance at a global conference on poverty, counter-cultural thinker and founder of the Emergence Network, Bayo Akomolafe, unpacked his above quote. Flipping the script that often frames “the system” as the cause of the world’s suffering, Akomolafe instead frames the system as a “consequence of our separation from each other.” A symptom, as it were. He goes so on to say “we are the system we fight against.”

Like Akomolafe, I believe there is a strength to be realized that has for too long lay dormant in the Western psyche. Patience and progress are not mutually exclusive. And progress is not synonymous with growth. To the contrary, hindsight often proves that what we look back on as “progress” was little more than stumbling in the dark guided by intelligent, but patient hands.

Another poignant example that reads like it could’ve been published yesterday is the “Keystone Principle,” from environmental policy expert KC Golden’s 2013 essay of the same name:

“Step one for getting out of a hole: Stop digging.”

Or simpler still, slow down!

The Absurd, the Naive, and the More Beautiful

The bottom line is this, we’ve known the primary drivers of climate change for long enough. The first step in order to redress the issue is to stop making it worse. And yet, we have done the literal opposite since Golden’s appeal during the Obama administration. Instead, the U.S. has only increased its oil and gas exports. It’s absurd.

We now find ourselves with little choice but to interrogate the absurd itself if we are to produce any lasting alternatives.

So, not unlike our hibernating kin, consider this a springtime pivot. the_slow_times hasn’t gone anywhere. But rather than write what I think I’m supposed to, I’m going to lean into my instincts. Progress may appear slow, but we owe it to ourselves and successive generations to document and engage in a meaningful exploration of not only climate science, but the very climate of change itself.

Root-branch solutions of the sort for which Akomolafe advocates can easily be dismissed as too costly, or worse, naive. But like Akomolafe, I truly believe how we respond will have a great deal to do with our effectiveness. At a certain point, it just comes down to physics. We cannot hasten a more beautiful world.

And if Akomolafe is right, that we are the very system we claim to fight, then our collective resistance to the blind forward march of the cult of speed will undoubtedly play a role in determining our future.

Slowly, but surely.

Climate • Culture • Change

I personally love the idea of a longer form media that allows us not only to read in chunks (slowly) but that actually encourages it. I may be slow by nature but I feel driven by the need to speed up. Nice to remember our minds and planet function better when we allow some slowness

Very thought provoking! Reminds me of "Hurry up and wait"

Thanks for sharing your writing!

😉