According to the London School of Economics, ‘stranded assets’ commonly refers to fossil fuel reserves and their constituent infrastructure that:

“may end up a liability before the end of its anticipated economic lifetime.”

This speculative designation explicitly prioritizes the promised profits of investors over the known degradation of ecosystems or the communities to whom these “resources” originally belong. That is to say, the integrity of the global financial system rests on realizing tomorrow’s ROI (return on investment) despite knowing today they come at a grave ecological cost.

Put another way, science is not in charge. Preserving the quarterly status quo trumps the concerns set to play out over the next quarter century. This perverse incentive structure remains the primary driver of the dual-pronged ecological and climate crises we face today and will serve as the bedrock of our investigation moving forward.

Stranded, Stunned, & Stalled

Assets can become liabilities for any number of reasons: government regulation, legal action, shifts in the marketplace, even natural disasters. Aside from the latter — over which even today’s economic elite have little control — those who stand to extract profits from fossil fuel investments have a vested interest in preserving their good standing with little regard for the downstream consequences.

“Most of the market risk falls on private investors, overwhelmingly in OECD countries, including substantial exposure through pension funds and financial markets.”

And yet, according to a recent study published in Nature, 60% of all known oil and gas reserves and nearly 90% of coal “must remain unextracted” if there is any hope of curtailing global temperature rise and limiting warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2050.

This means that if the world’s democratic governments were to act in accordance with leading scientific consensus, and in the best interests of the people whom they claim to represent, then the nearly $1 trillion valuation of these reserves and any existing infrastructure intended for their extraction must go unrealized.

This is no small demand. The implications of which are revolutionary. These so-called democracies have quite literally been tasked with charting a transition to a new world. A world that synthesizes economic prosperity and ecological harmony. And yet, little effort has been made to do so. Just the opposite in fact.

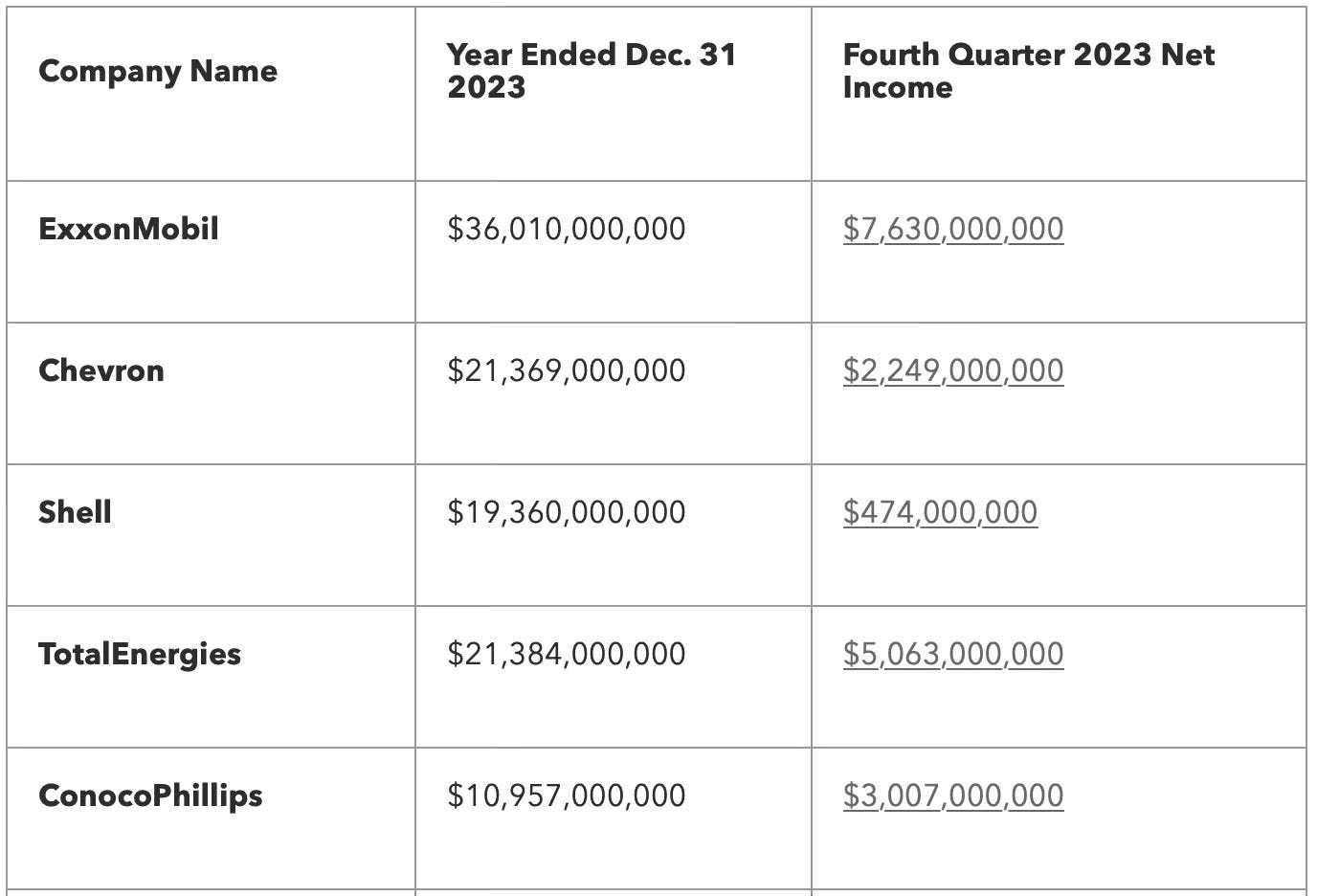

Multi-national oil and gas conglomerates have continued to post record profits, as the planet puts up record temperatures year over year, all while lobbyists assuage fears of continued exploration and exploitation.

We’ll always have Paris…right?

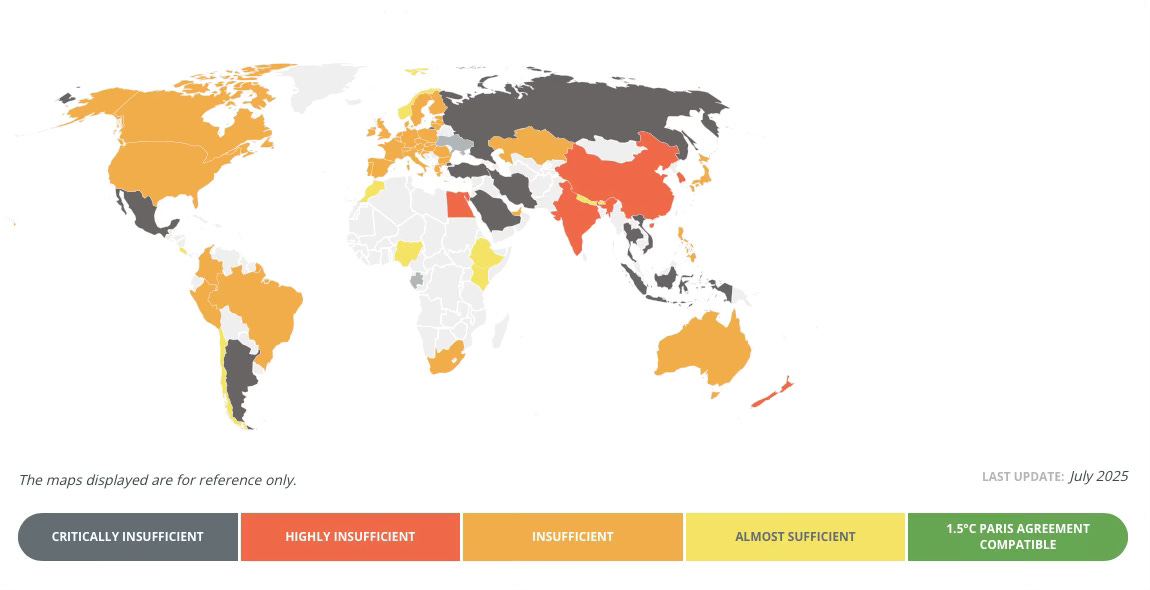

One of the seminal targets of the Paris Climate Agreement established the goal of limiting Earth’s warming to 1.5°C of above pre-industrial level. In the decade since, we are no where close towards realizing this goal.

According to the Climate Action Tracker, just seven of the 195 signatories to the agreement are “almost sufficient” at reducing their emissions to reach their target.

Among the mere seven nations that have made the most progress is Norway. A country that is currently one of the chief exporters of oil and gas around the globe and actively supports the further expansion of oil and gas exploration. By Climate Action Tracker’s own admission: (insert nifty accounting magic)

“The exported emissions from Norwegian oil and gas are not considered in the CAT’s overall “Almost sufficient” rating.”

Hardly a beacon of progress. But cutting against this myopic economic worldview is the still burgeoning field of Marxist ecology and the accompanying political project, eco-socialism.

From The Roots Up

Not much older than John D. Rockefeller’s monopolistic Standard Oil, the field of ecology grew organically out of the interaction between biology and the social sciences during the late-nineteenth century.

Despite some of the sordid seeds in science at the time (some early conservationists are known to have entertained ideas like eugenics, scientific racism, and a generally Euro-centric disposition), ecology evolved beyond these narrow views and is today tasked with examining the holistic relationship between organisms and their environment. The study of human ecology followed suit as anthropogenic impacts on the environment became increasingly relevant to our understanding of ecosystem dynamics and climate change today.

While not all ecologists endorse a historical materialist approach, those that do have made significant strides over the last half century. Scholars have recovered original ideas from significant socialist thinkers, including Marx himself, who is often misrepresented to have dismissed nature in his defense of labor. A closer reading through a modern ecological lens reveals both Marx and Engels to have celebrated a mature understanding of the relationship between man and nature, recognizing nature to be far more than the naive but picturesque wilderness ideal.

“The first object for man—man himself—is nature…” — Marx

A topic that certainly warrants further exploration at a later time, it was Marx’s analysis of German chemist Justus von Liebig’s soil science that informed his conception of what scholar John Bellamy Foster has termed a ‘metabolic rift.’ Recognizing the nutrient depletion as a result of a profit-driven agricultural project devoid of natural balance, Marx’s analysis of the issue offered something of a precursor to today’s ecological critique of industrial agriculture.

Conversely, there are those within the eco-modernist camp that like to profess advancements in technology will naturally temper the degradative impacts of economic hegemony. But the rapacious appetite for consumption at the heart of the capitalist project routinely proves that advances in efficiency rarely reduce consumption, but rather increase overall consumption as it becomes more efficient to do so. (Think, have you ever seen traffic improve with the addition of another lane?)

As it relates to the modern notion of stranded assets, political economist and professor of sociology, James O’Connor, helped bridge these symbiotic worlds when he coined the first and second contradictions of capitalism:

The absolute general law of capitalist accumulation.

The absolute general law of environmental degradation under capitalism.

In his book The Ecological Rift, John Bellamy Foster points out that, while the second law relies on the first, it is the latter that poses the most obvious challenges for capitalism today.

In other words, the ecological degradation at the root of capitalist expansion is the driving force of stranded assets of all kinds — well beyond the purblind fixation on fossil fuels and tangential infrastructure by the financial sector.

What we’re willing to lose…

Bringing this introductory article to a close, I want to stress the severity of the moment in which we find ourselves. The ideas borne out in pages of theory over the past two centuries are today anything but theoretical. Whether ecological, political, or social, the global community is in a state of tumult the likes of which hasn’t been seen for decades but has been foretold.

Those who cling to quotidian norms are the same class who have long feared even the most benign regulations. Meeting our moment cannot be achieved by well-meaning reform along the fringes that preserves the very system that produced the crises today’s generations have been tasked to solve.

Put another way, you and me, our loved ones, and the world we love are being left for stranded. Whether it is our public lands, food sovereignty, or even basic human rights, these are the true assets worth fighting for tooth and nail. These are the lines we must draw and refuse to cross. This is an ecological revolution.

We have a world to win!